How did nursing staff deal with infectious diseases in the 19th century? Stuart Wildman, Chair of the RCN History of Nursing Forum, finds parallels with the COVID-19 pandemic in one nursing student’s notes

In the past, epidemics of cholera, typhus, typhoid, smallpox and influenza were serious threats to public health. Other infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis, diphtheria, measles, scarlet fever and whooping cough were endemic. They all had the capacity to kill or disable.

Scientific advances – new vaccines, antibiotics and antiviral drugs – have meant we’re much better protected than our Victorian and even 20th-century counterparts. Yet the emergence of the COVID-19 virus sent us back in time. With no known cure, health workers have had to introduce measures to prevent the disease spreading, whilst protecting themselves and supporting their patients’ vital functions. In principle, nursing practice in the late 19th century was not all that different.

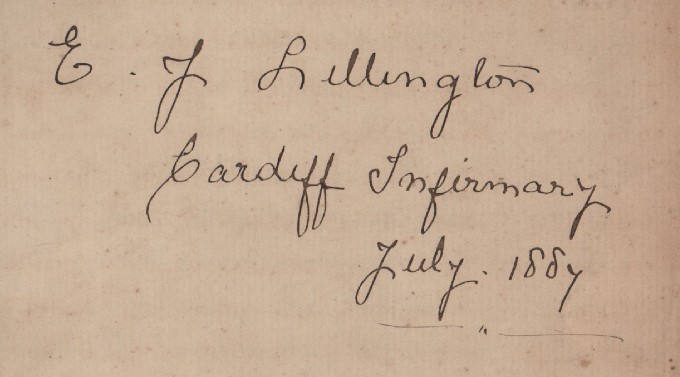

In 1887 Eliza Jane Lillington (pictured above), aged 26 and from Bristol, started her nurse training at Cardiff Infirmary. She undertook standard one-year training, receiving her certificate in 1888 and returning to Bristol as a district nurse. She married in 1890 and although she is listed in Burdett’s Official Nursing Directory of 1898, it is unlikely that her career lasted that long, having had four children before the end of the century.

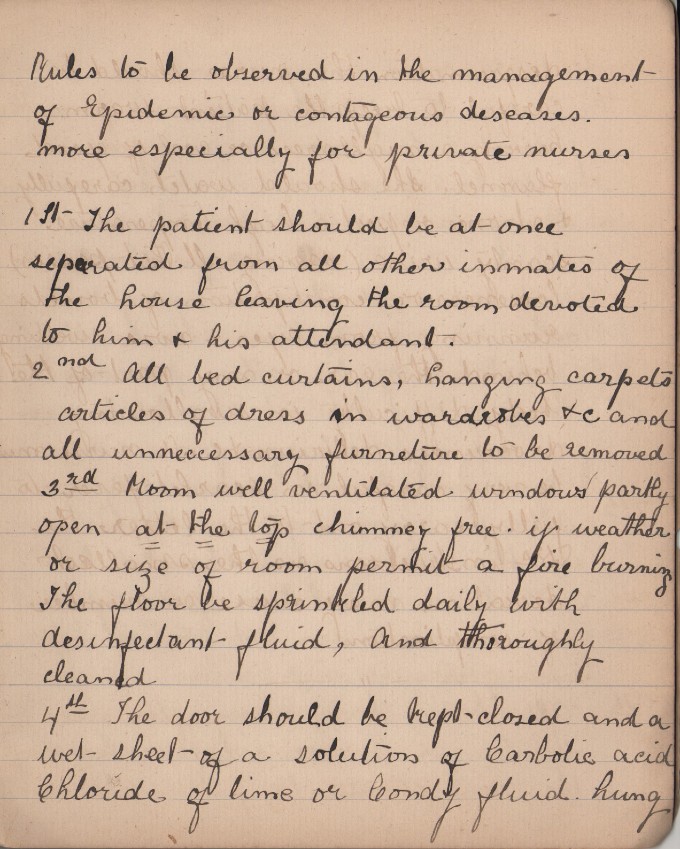

One of her exercise books from 1887 contains rules for managing patients with contagious diseases, as well as notes on smallpox, scarlet fever and typhoid. Although bacteria that caused some diseases had been identified by this time, viruses remained undiscovered. As a result, blanket measures were applied to prevent the spread of infection by controlling the patient’s environment and destroying pathogens.

Late 19th-century textbooks emphasised the need for isolation, ventilation, cleanliness and disinfection in infectious cases. These principles can be seen in Eliza’s notes (pictured above) for nursing a patient in a private home. The patient was confined to one room, with no visitors other than the nurse and doctor allowed. All unnecessary items, including curtains and carpets, were removed. The room was constantly ventilated by keeping a window open slightly and having a fire burning night and day to cause a through-draft of air. The floor and all surfaces were cleaned daily using a disinfectant and all utensils, bedding and patient clothing were disinfected before leaving the room. Patients were observed and supported by a nurse until they recovered or died.

Similar precautions are still applied today. People who have symptoms of COVID-19 are asked to isolate, specific hospital wards are allocated for the very ill, patients are supported constantly by nursing staff, disinfectants are used to keep surfaces virus-free and new research has shown that better ventilation decreases the viral load of the air.

However, in contrast, little in the way of personal protective equipment was available to 19th-century nurses. Eliza was advised to wear a uniform that was easily washable, to keep her hands very clean and to avoid inhaling the patient’s breath or “other emanations”. It is no wonder that Florence Nightingale reported that nurses were three times more likely to die of infectious diseases in the 1850s than the general population of women. Smallpox and other infections continued to kill nurses into the 20th century despite better knowledge and treatment.

While we began facing COVID-19 with an insight into the experiences of the Victorians, the advanced state of medical research today means that 12 months on, vaccines have already been produced and the end of the pandemic may be in sight. However, more than 900 UK health and care workers have lost their lives to COVID-19, in part due to an initial lack of PPE.

Outbreaks of novel infectious diseases will undoubtedly occur in the future and nursing staff, just like Eliza before them, will have to learn how to deal with new threats. Just as important, future governments will have to be better prepared.

Join the History of Nursing Forum

Find out more about the RCN's History of Nursing Forum here.