Professor Peter Nolan spent more than 50 years working in mental health services in the UK and abroad. Over time, he noticed a gap between what psychiatric nurses were taught and the stated aims of mental health services, and the reality of work and conditions for both patients and nurses.

In 2020, during a talk for the RCN, he said: “I started psychiatric nursing in the early 1960s. Most of what I learned about mental health and illness was through listening to stories.

“Nearly a third of all the male nursing staff in hospitals at the time had spent some time in the forces. Some had seen acts of service in the Second World War, the Korean War, Suez, and some had done national service.

“I became fascinated with mental health nurses, their reasons for becoming nurses and what they believed they were doing.”

Professor Nolan’s observations and interest in the profession led him into research. Much of his research work has focused on the experiences of patients within mental health services and the nursing staff who are charged with their care.

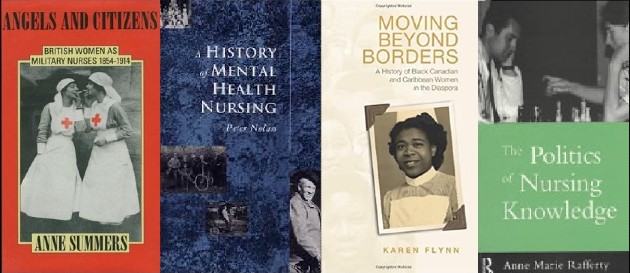

In the early 90s, his first book, A History of Mental Health Nursing (pictured below), was published. In it, he traced the roots and evolution of mental health nursing – from the role of ‘keeper’ and the setting of workhouses and asylums, to the development of a specialty area of nursing and emphasis on community care. He spoke to fellow nursing staff, mental health patients and their loved ones to paint a complex picture of this area of care.

Elsewhere, he wrote about violence within mental health services, as experienced by mental health nurses and psychiatrists. In 2016, he teamed up with Niall McCraw, a lecturer in mental health nursing at King’s College London, to write The Story of Nursing in British Mental Hospitals. The volume covered the history of mental health nursing from the late 19th century to the end of the 20th century in great detail, with illustrative anecdotes.

As Professor Nolan told the RCN, he was fascinated by the anecdotes of individuals and shared one particular story that had stuck with him for decades.

Jack, a retired psychiatric nurse, was the first former prisoner of war (POW) that Professor Nolan interviewed. “That meeting is as vivid in my mind today as it was that afternoon,” he said. Jack was flattered to have been asked to speak about his life, but it soon became clear that he had kept details of his past hidden. “Though he thinks a lot about the past, he rarely speaks about it,” Professor Nolan said.

Born in 1918, Jack had a happy childhood in the west country. Aged 14 he left school and got a job at a factory where he joined the football and cricket team – at which he excelled. After seven years, he was called up to serve in World War Two.

One of Jack’s lasting memories of his early days in a mental hospital was the amount of violence he witnessed

He was excited to fight for his country and was serving alongside his childhood friend Alfie. But their time on the frontline was short. They took part in a 1940 campaign in France and were taken prisoner. From May 1940 until 1945, he was in POW camps in Poland and Germany.

He was forced to work relentlessly, march over long distances and was constantly near starvation. He told Professor Nolan that death was everywhere – he’d see bodies in ditches and hanging from trees, while his fellow POWs suffered from illnesses. He told Professor Nolan: “My lowest time came when I saw Alfie shot by the SS. I was only 20 yards away.”

Recounting these traumatic experiences, Jack broke down – he had never shared these details with anyone.

After the war, he couldn’t settle back into his old life. He contacted a friend, a mental health nurse, and joined the profession.

Professor Nolan says: “His first encounter with patients made him feel uncomfortable. These unhappy, disturbed individuals were not what he expected and he considered leaving.”

But he didn’t. He enjoyed the company of colleagues, many ex-servicemen like him, and playing on his hospital’s sports teams. He’d also begun studying for a psychiatric nurse qualification and enjoyed learning and attending lectures.

However, after gaining his qualification, he didn’t always get to do the type of nursing care he had learned about. Often, he said, he felt more like a warder.

He wanted to be involved in teaching student nurses the proper way of caring for psychiatric patients

Professor Nolan says: “One of Jack’s lasting memories of his early days in a mental hospital was the amount of violence he witnessed. Some nurses were of the opinion that all the patients were in a conspiracy to make life as difficult as possible for the staff.

“Jack was drawn into this way of thinking and admitted there was gratuitous violence against patients. He too was aggressive towards them.”

Some patients had developed mental health issues as a result of their wartime experience. Rather than empathising, Jack felt they were weak – this sometimes caused him to lash out.

Professor Nolan recalls: “He said he had a ‘need to get my own back’ having taken so much abuse at the prisoner of war camp.”

Talking to Professor Nolan, Jack expressed remorse for his past behaviour. Professor Nolan says: “Nearly 20 years after he started nursing, Jack held the post of charge nurse, he began to think seriously about his past… he became aware he had used nursing for his own ends and entered what he referred to as his atonement phase.

“He took a keen interest in all the patients on his ward and organised parties and outings for them. He wanted to be involved in teaching student nurses the proper way of caring for psychiatric patients.”

He became one of the first nurses at his hospital to get involved with mental health care in the community. His first patient to transition from hospital to community was an old soldier called Lionel who had been a POW in a Japanese camp. He told Professor Nolan: “When I knew he was settled and happy in his little flat, I felt a profound sense of satisfaction… The fact he was an ex-POW like myself made me feel even better.”

After retiring, Jack was still committed to the care of the mentally unwell and volunteered at the mental health ward he started his career on.

Peter says: “Talking about his experiences caused him great distress… [but] he was relieved to be able to tell his story.”

He said if he had his time again, he’d still be a mental health nurse.