Gosia Brykczynska explores the lasting legacy of nurse Kate Marsden’s Siberian mission to treat leprosy

Kate Marsden was born in Edmonton, London in 1859. Yet it was in the distant Siberian province of Yakutia where she made a lasting impact as an innovative and compassionate nurse.

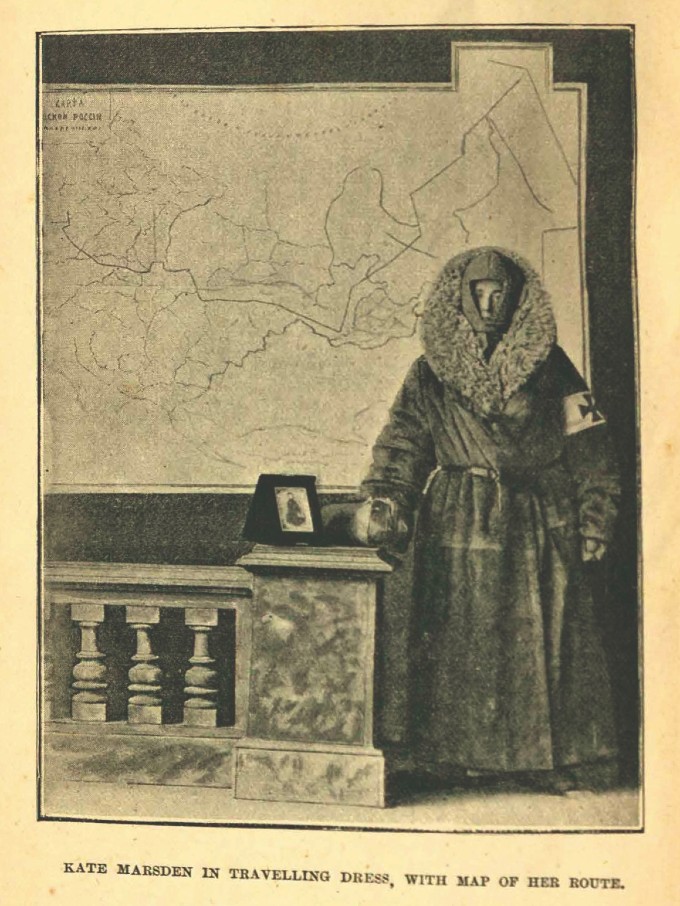

Soon after her training in Tottenham, London, Marsden volunteered as a Red Cross nurse in Bulgaria during the Russian-Turkish war, looking after Russian soldiers. It was here that she first encountered people suffering from leprosy. She later wrote in her memoir: “Surely these, of all afflicted people, ought to become the object of my mission.”

Marsden learned there was a herb that could cure the disease – but it grew only in Siberia. She was determined to find it. Her career continued as a matron in New Zealand and elsewhere, but by 1890 she found herself in Russia to receive an award for her Red Cross work. Determined to find the cure for leprosy, she met with the Empress of Russia and secured her support. She also sought funds in continental Europe and the USA, and received the backing of Queen Victoria.

In 1891, after an 11,000-mile journey, Marsden finally reached the people afflicted with leprosy in Yakutia, Siberia. Unfortunately, the fabled herb did not have the power to treat leprosy, but Marsden did set up a hospice and treatment centre.

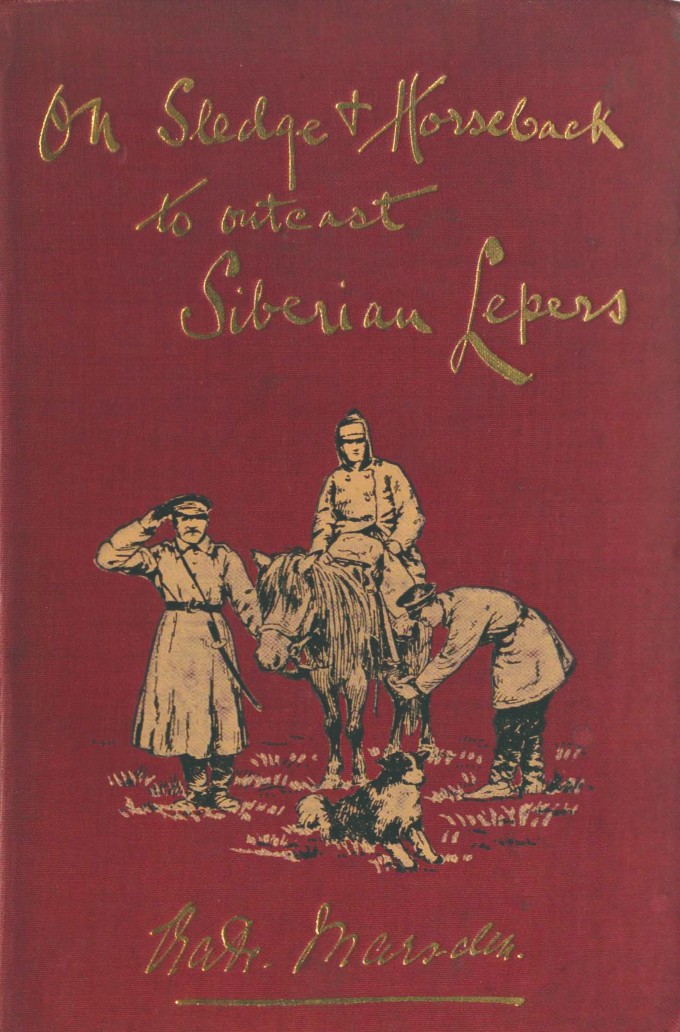

Marsden published an account of her expedition, On Sledge and Horseback to Outcast Siberian Lepers in 1893. Her Siberian mission saw her elected one of the first women fellows of the Royal Geographical Society.

Back in England, she faced many obstacles and much criticism for her feisty temperament, rumours about her sexuality, and antipathy towards Catholicism. She had converted to Catholicism and helped set up St Francis Leprosy Guild in 1895, to care for leprosy patients around the world. This association still exists and over the past 125 years has cared for hundreds of thousands of leprosy patients. Marsden stepped down from this work soon afterwards and went to live with friends. She died in poverty in 1931, largely forgotten.

However, the people of Yakutia did not forget her. They have expressed their gratitude for her work by naming a medical school and a square after her, erecting a statue and printing her picture on stamps.

Last year, the people of Yakutia arranged to have a new memorial stone blessed and put on her grave in Hillingdon, West London. A group of Russian Orthodox worshippers from Yakutia with their bishop, Russian consulate officials, local English dignitaries, representatives from the leprosy guild, and Heather Bond representing the RCN History of Nursing Forum, gathered at Marsden’s graveside.

The moving event brought home the irony that Marsden, who led such a rich life and touched so many individuals, died in obscurity. Her memory lives on in Yakutia, over 4,000 miles from where she now lies at rest.