Prison Nursing Unlocked explores the little-known history of prison nursing and the vital contribution that nurses make to prisoner welfare today.

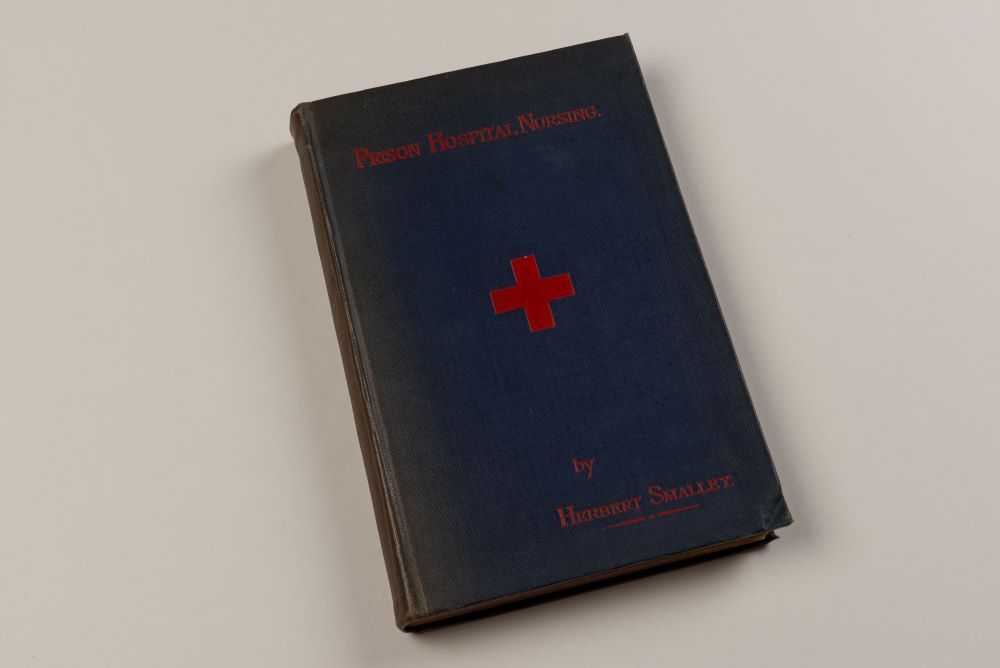

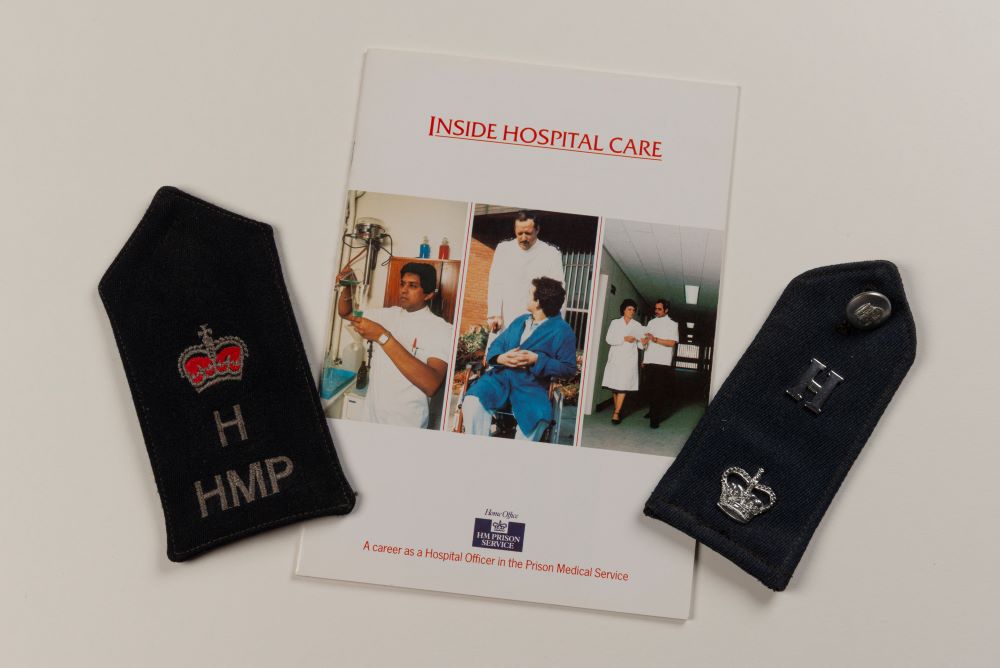

Today, nurses play a vital part in prison health care. However, the role of the prison nurse has a surprisingly short history. As late as the 1990s, most prisoners received nursing care from prison officers with basic health care training.

Prison nurses bring a wide range of specialist skills to provide compassionate care in a uniquely challenging environment. They must tread a fine line between care and custody, recovery and rehabilitation. However, at the heart of their work is ‘equitable care’ – ensuring that people in prison receive the same quality of health care as those in the community.

Prison Nursing Unlocked has been co-created with Royal College of Nursing members, many of whom currently work as prison nurses, or have in the past.

Early prison reform

For centuries, the health of prisoners was largely ignored. Prisons were temporary holding places before public punishments like whipping, transportation abroad or the death sentence. Conditions were filthy, disease was widespread, and prisoners had to pay their own jailers’ wages, encouraging corruption.

A right to basic health care

By the 1770s, the social reformer John Howard called for a drastic overhaul of the prison system and insisted that prisoners had the right to basic health care. Horrified by conditions he had seen firsthand, he successfully campaigned for the introduction of a surgeon into all prisons in England and Wales. He also recommended that nurses be employed in prison infirmaries, but his advice was not followed for another hundred years.

Prison matrons

In 1813, the quaker reformer Elizabeth Fry began visiting Newgate Prison and became particularly concerned about the welfare of female prisoners. Her campaigning led to the introduction of female ‘wardresses’ for female prisoners and the development of the role of ‘prison matron’. However, the matron’s primary focus was on discipline rather than prisoner health.

Image Above: Elizabeth Fry visiting Newgate Gaol. Credit: The Wellcome Collection

Prison care and justice for women

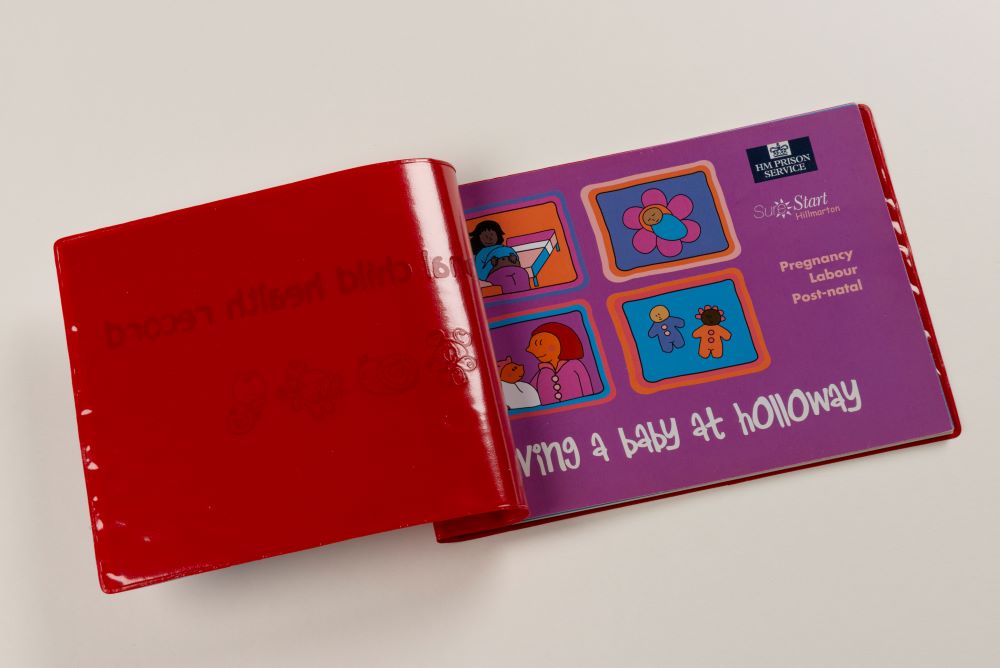

The first trained prison nurses didn’t appear until after the First World War. At first, they only worked in women’s prisons. Their introduction was part of urgent reforms to address female health needs such as maternity care.

In 1919, HMP Holloway in North London became the first prison to employ trained nurses. Then the largest women’s prison in Europe, it held up to 950 female prisoners with a medical staff of just 4 doctors. All other care was carried out by ‘wardresses’ who had little or no nursing training.

Nurses were introduced following a critical enquiry, which uncovered failings in Holloway’s care for women and babies and the need for prison staff trained in midwifery.

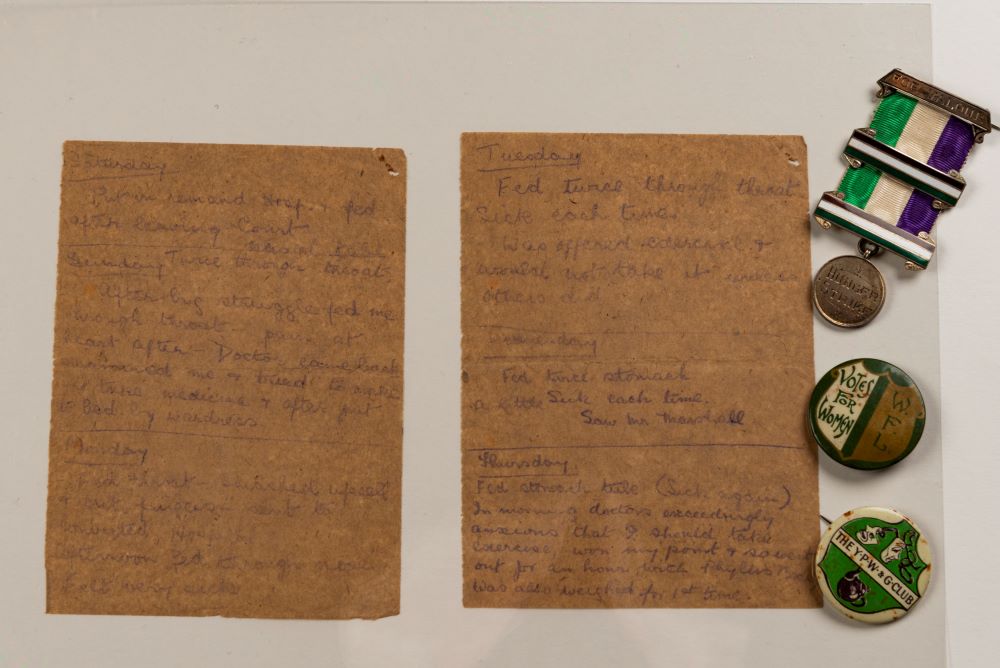

The fight for the vote

Conditions at Holloway Prison had also been thrown into the spotlight by the wider battle for women’s rights. Between 1906 and 1914, almost 300 suffragettes were imprisoned at Holloway and many experienced brutal force feeding at the hands of its medical staff.

Nurses were amongst those who joined the public outcry and pointed out that there were no nursing staff onsite to help suffragettes recover after this ordeal.

The First Prison Nursing Service

By 1928, Holloway had the first Prison Nursing Service, training nurses who could then work in other prisons across the country. However, prison nurses continued to work primarily in women’s prisons until the 1980s.

Image: Prison nurses and other prison staff outside HMP Holloway, 1920s-1930s. Credit: National Justice Museum.

Patient or prisoner?

Working in a prison, every day comes with different challenges, but it can be a truly humbling place to work. Given certain circumstances, anyone can come through the criminal justice system.

Lauren Hendy, Specialist Clinical Nurse Prescriber at HMP Eastwood Park

Prisons have had their own medical service since 1877. However, even after the NHS was founded in 1948, prison health care continued to be managed by the Home Office.

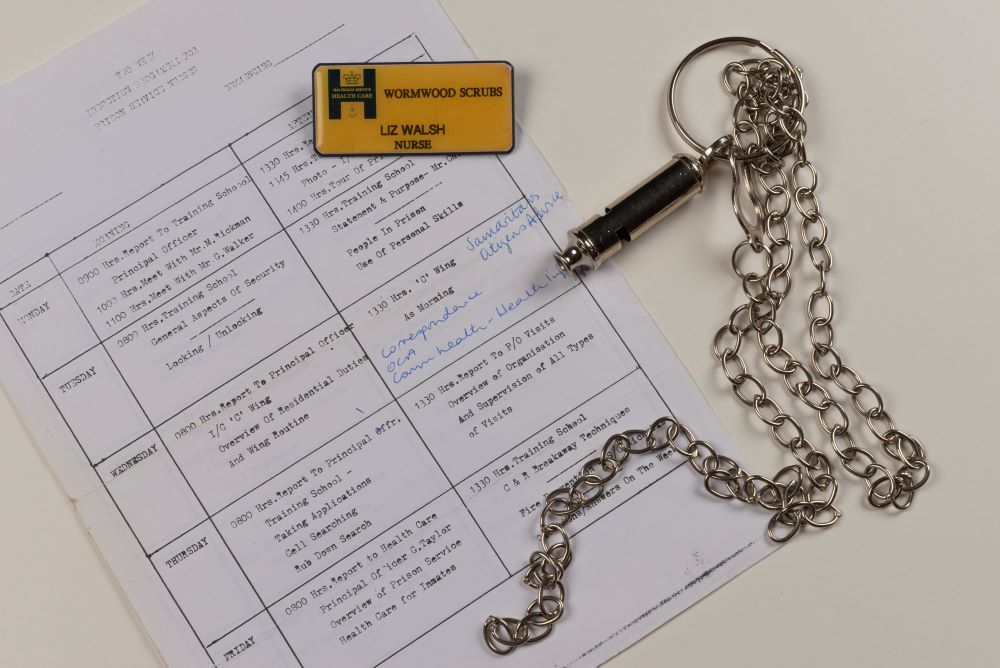

Although some registered nurses were working in prisons, for much of the twentieth century, nursing care was provided by ‘hospital officers’ – prison officers with just six months health care training. In 1996, a Home Office report, 'Patient or Prisoner,' criticised this approach, arguing for ‘equivalence’ in prison health care. In other words, prisoners have a right to the same level of care as the rest of society.

This led to calls for prison health care to become part of the National Health Service. Ten years later, criminal justice nursing in England and Wales was brought into the NHS (2011 in Scotland and 2012 in Northern Ireland). Today, the principle of equitable health care remains at the heart of prison nursing, whether it is delivered or commissioned by the NHS.

Image: Prison nursing team who won a 2020 RCNi Nurse Award for their work supporting prisoners with learning disabilities at HMP Parc. Credit: RCNi.

An equal right to care

Prison health care services today are mainly nurse-led, although prisoners can also access clinics run by GPs, dentists, psychiatrists and other specialists. Growing numbers of registered nurses and health care support workers are employed as part of the multidisciplinary workforce in prisons.

Nursing in justice settings is not easy. More than 20% of prisoners are held in conditions classed as crowded. Physical and mental health problems are widespread. Alcohol and drug addiction is common.

This exhibition aims to show that, despite these challenges, nursing staff have championed change in prison settings since the early twentieth century – working to improve maternity care, provide trauma-informed mental health support and dignified end of life care in prisons. Today, equitable healthcare for all regardless of individual circumstances remains at the heart of prison nursing.

Exploring and Celebrating the Role of Prison Nurses at HMP Eastwood Park and HMP Warren Hill

Prison Nursing Unlocked featured artwork created by people currently serving sentences at HMP Eastwood Park and HMP Warren Hill as part of a partnership between Koestler Arts and the RCN Library and Museum.

Participants were invited to workshops led by prison art tutors in their respective establishments to celebrate the vital role of prison nurses creatively. They produced artworks exploring themes including care, resilience, and humanity, creating meaningful pieces across different mediums that reflect their own perspectives and experiences.

Credits

With special thanks to our volunteer team of RCN members who co-curated this exhibition with the RCN Library and Museum team, with support from the RCN History of Nursing Forum, the RCN Forensic and Justice Nursing Forum, and the RCN Archive team.

With thanks to the Koestler Trust and to workshop participants at HMP Eastwood Park and HMP Warren Hill. Thanks too to our lenders and to everyone who has contributed a story, experience, photograph, or object to the exhibition.

Exhibition research was led by Antonia Harland-Lang and contributed to by Elaine Beddingham, Jill Bowman, Sarah Chaney, Claire Chatterton, Kai Flynn, Lauren Hendy, Sarah Jarvis, Shelley O’Connor,

Sue Yasee, and Victoria Nwaoha.

Exhibition design by Sharon Lockwood.

Object photography by Martyn Milner.

Exhibition webpage built by Heather Taylor.